Non-Coercive De-Escalation

At some point in your job as a clinician you will encounter an aggressive individual. The situation is often tense and can quickly escalate beyond the necessary proportions. Think back to the last time you had to deal with an aggressive patient or relative. How did you manage it? This article discusses different de-escalation strategies you can use in order to reduce the chance of aggression escalating into conflict.

An Introduction to Non-coercive De-Escalation

Aggressive individuals are encountered in many different settings; it might be in the GP practice, in the emergency department, on the wards or in clinic. These individuals might be patients, they could be relatives of a patient, friends of a patient or even a colleague! The reasons for their aggression will vary greatly and may even be organic in nature.

Non-coercive management of aggression involves engaging the aggressive individual verbally, forming a collaborative relationship and working to verbally de-escalate them from their agitated state. This occurs without the use of force or threats to achieve compliance.

Goals of De-Escalation

- To ensure the safety of the angry individual, patients, staff and others in the area.

- Help the angry individual manage their emotions and distress.

- Help the angry individual maintain or regain control of their behaviour.

- Avoid the use of restraint where possible.

- Avoid coercive interventions that could result in escalation of agitation.

Getting Started

In the first instance, it is important to engage the individual and help them become an active partner in de-escalation. This involves the use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the aim of helping the individual calm themselves down as they re-establish their own internal locus of control. Verbal de-escalation is usually successful within five minutes, although a little additional time may be needed for more complex cases.

Begin by introducing yourself; state your name and role and find out the name of the individual. Explain that you want to help but also set firm boundaries. Then give some time for the patient to state their concerns. Do not give your opinions on the issues, especially those beyond your control. You should attempt to identify the trigger for the escalation in their behaviour and manage them where possible. If there are any unmet needs, try to correct those that can be easily remedied (i.e. pain control). If a decision needs to be made, give them time to consider what has been said. Remember that silence is a useful tool for helping individuals reflect on their actions. Finally, recruit trusted friends or relatives to help improve the situation.

In some instances, there will be patients you cannot de-escalate. This commonly occurs in delirious patients and may also be seen with psychiatric patients. In these cases, you should be persistent with your attempts at verbal de-escalation and only use medication as a last resort. Be sure to recognise your limits; de-escalation can be mentally taxing and may place you in harms way. If you feel as though your safety or that of others is at risk, you should seek assistance from security straightaway. The presence of security may help persuade individuals to co-operate.

Early Recognition of Agitation

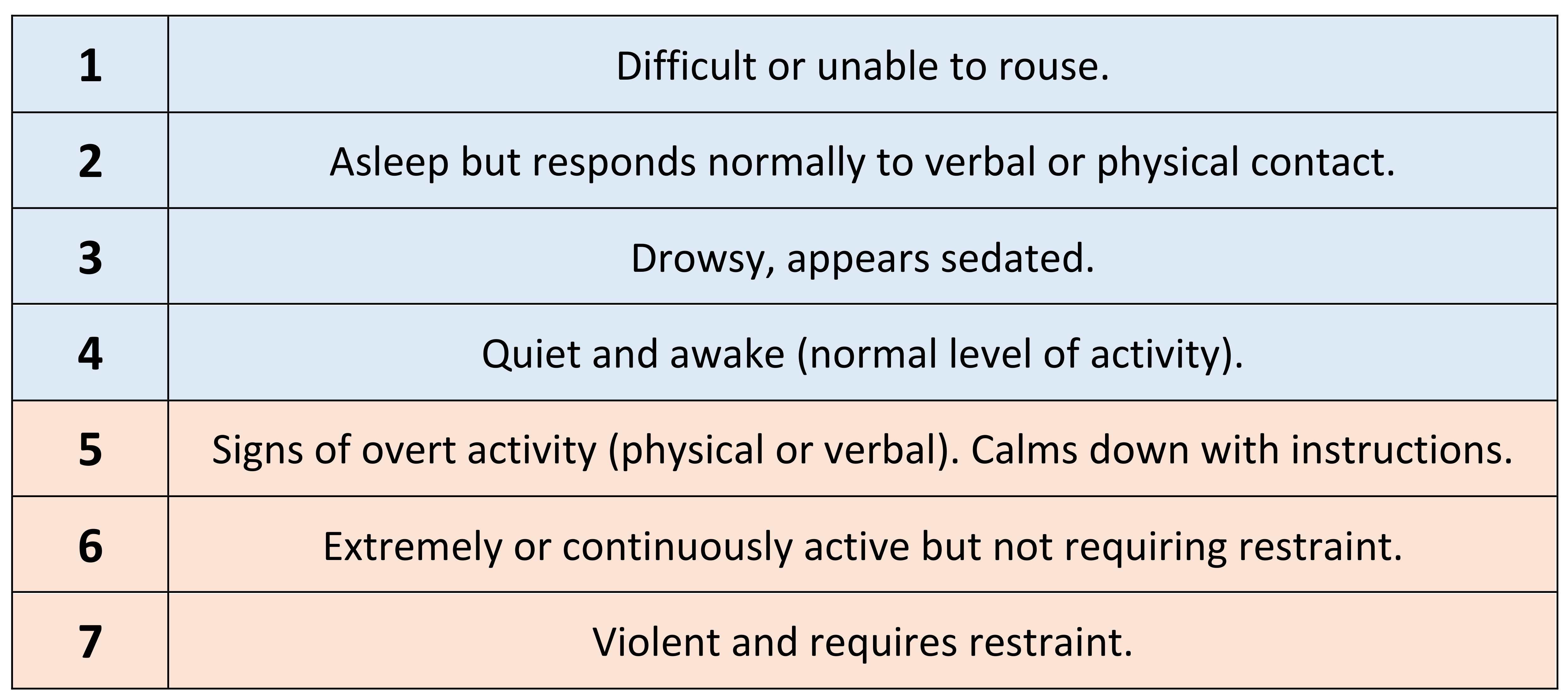

Early recognition of agitation can lead to early de-escalation and resolution of any conflict before things spiral outwards. Use of an objective scale to monitor agitation can help in these regards. One example is the Behavioural Activity Rating Scale (BARS). Any patient or individual who displays signs meeting level 4+ should be reviewed and attempts made at de-escalation. Signs of early restlessness might include foot tapping, hand wringing, hair pulling, repetitive thoughts, irritability or heightened responsiveness to stimuli.

Types of Aggression

Psychologist Kenneth Moyer identified eight types of aggression during his work in 1968. They are predatory, inter-male, fear-induced, irritable, maternal, territorial, instrumental and sex-related aggression. Several of these forms might be seen in aggressive individuals in the workplace. They are as follows:

Instrumental Aggression

This is aggression directed towards obtaining a goal and is not driven by emotion. It may be a learned response and can be handled by using unspecified counter offers. For example, you might suggest enacting their threat is not a good idea. If they ask, “What do you mean?”, you will respond with “let’s not find out”.

Fear driven aggression

This is aggression associated with attempts to flee from a threat. They do not want to be hurt and may attack to prevent someone hurting them. Give them plenty of space and do not intimidate the patient or make them feel threatened. Match the patient’s pace until they start to focus on what is said, rather than the fear they feel.

Irritable Aggression

This is aggression induced by some frustration and directed towards an available target. There can be many different causes, but two common types are described below.

- Violated boundaries. This occurs when someone feels cheated, humiliated or emotionally wounded. They are angry and trying to regain their self-worth and integrity. They want to be heard and have their feelings validated. In these instances, you might try to agree with them in principle.

- Chronically angry at the world. They give no reason for their anger and need to release the constant pressure they feel as a result of their world view. They make unrealistic demands, use them as an excuse to attack out and enjoy creating fear and confusion. Do not offer them a response to their demands. Make attempts to remove all unnecessary people from the area. When interacting, use emotionless responses and offer them choices rather than the violence they want.

General Guidelines for De-Escalation

The following guidelines are based on the Best Practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation (BETA) guidelines as described in a consensus statement on the verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient.

Preparation and the Environment

Training with de-escalation techniques is an important step for preparing to deal with an aggressive individual. Reading this article is a good first step, but you can go further and ask your department for role play or simulation to practice the skills in real time. Other useful interventions include designing spaces for safety or ensuring your department is adequately staffed, although these cannot be made during the heat of the moment.

Anyone can learn the skills and techniques needed to be successful at verbal de-escalation. The most important thing to bear in mind is that you must start with a good attitude towards the individual. Hold them in a positive regard and try to empathise with them. Recognise that they are probably doing the best they can under the current circumstances, whether there is an organic cause driving the aggression or not.

There are some small adjustments that can be made to the environment during the acute management of an aggressive individual. Try to make a safe space by removing furniture or any objects that can be thrown or used as weapons. Make efforts to ensure exits remain free and accessible for both staff and the aggressive individual. If possible, move away from public spaces to a private area to talk.

General De-escalation Guidelines

If you become overrun with emotions or are frightened of the aggressive individual, this will impact your ability to work. Monitor your own emotional and physiologic response and try to remain calm. Remember, the majority of information is conveyed by body language or tone of voice. BETA have identified 10 domains of de-escalation that help clinicians care for agitated patients.

Respect the patient’s personal space

Do not be provocative: avoid iatrogenic escalation

Establish verbal contact

Be concise: keep it simple and use repetition

Identify wants and feelings

Listen closely to what patient is saying

Agree or agree to disagree

Lay down the law and set clear limits

Offer choices and optimism

Debrief the patient and staff