Advocacy with Inquiry

Advocacy and inquiry are two communication techniques, which if used in concert, can produce revealing insights and lead to positive changes at a personal and organisational level. See our education article on Debriefing with Good Judgement for an example of how it might be used. But what exactly is advocacy with inquiry and how can it be used effectively?

What is Advocacy and Inquiry?

Advocacy with inquiry is a powerful technique which promotes discussion and helps identify the underlying drivers of thought or behaviour. The two components are as follows:

Advocacy

This is stating one’s view. It involves an assertion, observation, hypothesis or statement.

Inquiry

This is a question. It involves testing the view delivered in the advocacy.

Conversations based upon these two components are driven by the assumption that you are missing things that others can see, and that you can see things that others are missing. Furthermore, the actions that others take are made with integrity and will make sense to them with their own perspective of the situation. Understanding the other person’s viewpoint will help break down barriers and foster mutual learning.

Difficulties of Unilateral Control

The use of advocacy with inquiry helps prevent a state of unilateral control, our default stance in discussions. Unilateral control describes the situation in which one’s decision to exert control is made without consultation or discussion (hence unilateral) and where our actions attempt to control the decisions or reactions of others (hence control). It might include the withholding of information in order to not upset the other person or perhaps divulging certain information to ensure we get our own way.

Unfortunately, unilateral control is seldom the most effective communication strategy for achieving progress. The actions taken as a result of unilateral control are based upon assumptions of what others are thinking and these assumptions are frequently incorrect. These mistakes will persist because individuals rarely put their assumptions to the test. Consequently, opinions and actions formed as a result of discussions are adversely influenced. An example of this would be attempting to avoid causing offence: this is counter-productive as it effectively silences the other participant for their “protection” and prevents the sharing of different views.

Introduction to Mutual Learning

The solution to all these problems is to seek genuine dialogue which can be achieved through advocacy with inquiry. Advocacy with inquiry helps counter unilateral control through a process known as mutual learning. This describes the outcome of a discussion in which both parties are active and valued participants. In such discussions, both parties will share their thoughts and give valid information while actively encouraging the other to share what is on their mind, even if it is a different view from their own. This form of two-way communication ensures that everyone’s view is heard and understood.

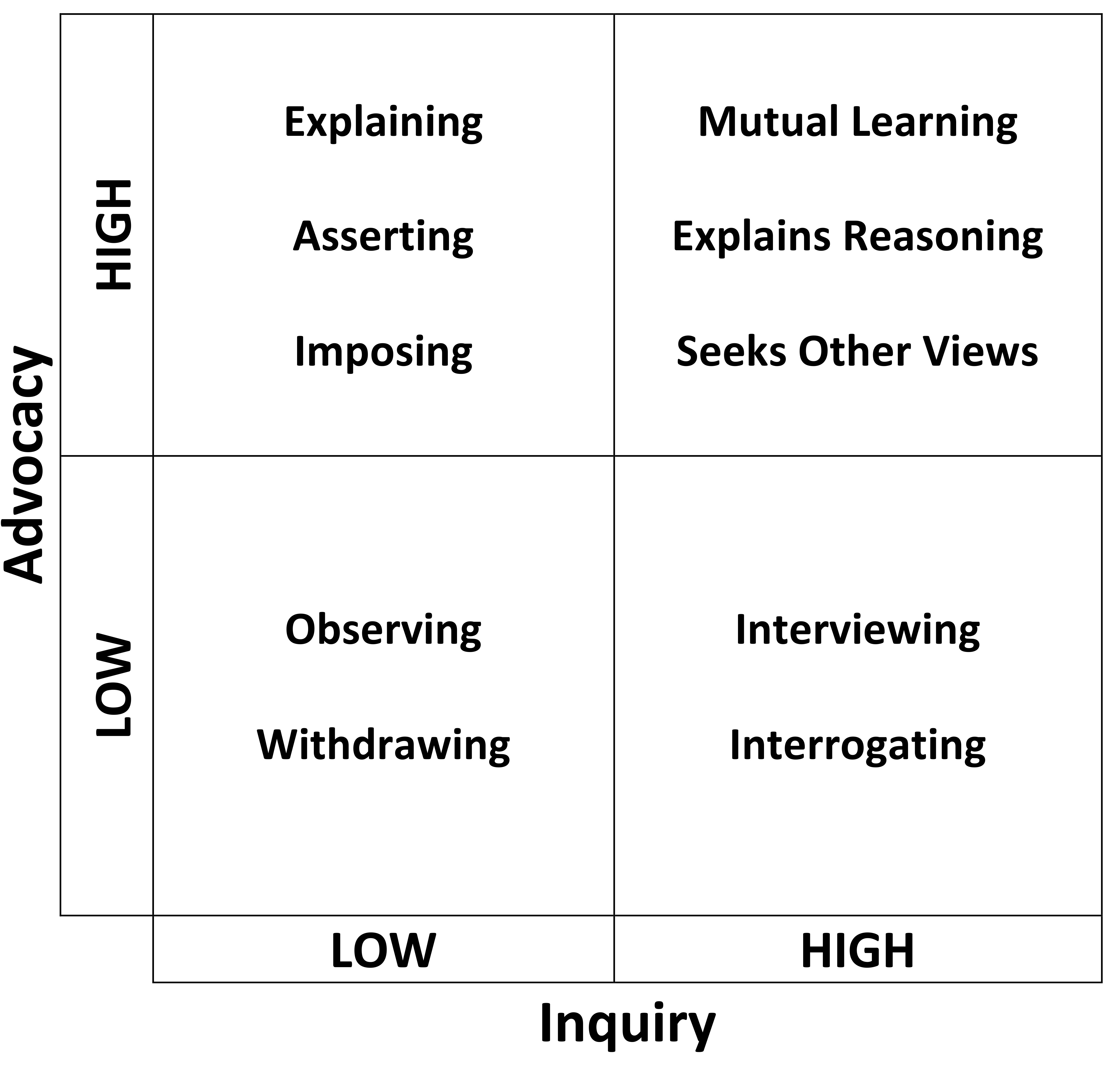

Achieving a Balance between Advocacy and Inquiry

As with any behaviour, there is a fine balance between excessive and insufficient use. The same can be said for both advocacy and inquiry. Finding the right balance between the two behaviours will help you determine how best to contribute at any given time. For example, if individuals are making many assertions but not asking questions you might inquire into their views before adding your own. Alternatively, if individuals are asking lots of questions without giving their opinion you might advocate your view to move the discussion forward.

Low Advocacy and Low Inquiry

Information flows in one direction as individuals are reluctant to ask questions and predominantly observe without contribution. It leads to views on key issues being withheld. This behaviour is usually driven by participants worrying about appearing uninformed, lacking initiative or being afraid to challenge another persons’ credibility and authority.

High Advocacy and Low Inquiry

Information flows in one direction, even if both individuals are speaking. It is useful when giving information but does not enhance understanding of different perspectives or help to build a commitment to a course of action. Furthermore, listeners may feel the speaker is imposing a view on them without taking into account their perspective. When these views are imposed it can lead to either compliance conflict or withdrawal from the interaction. It may commonly occur with complex or controversial topics.

Low Advocacy and High Inquiry

Information flows in a trickle. Asking questions without stating views makes it difficult to know where others stand. While it might help with finding out certain information, the lack of progress will lead to frustration and feelings of impatience. Further difficulties arise when the speaker has a hidden agenda and is using inquiry to get the other person to “discover” what the speaker already thinks is right.

High Advocacy and High Inquiry

Information flows in two directions and enhances the understanding of each other’s views. This leads to progress as agreements can be reached on the next course of action. State your views and inquire into theirs. Invite others to state their views an inquire into yours. High advocacy and high inquiry involves:

- Explanations of views with illustrative examples.

- Seeking the views of others.

- Probing the view of others.

- Challenges to current thought processes.

A Question of Quality

Reaching a balance between advocacy and inquiry is important to ensure two-way communication. Discussions high in advocacy will cover a lot of ground as they move quickly from point to point, while inquiry will slow the pace of conversation and increase the rate of learning. But what exactly does high quality advocacy and inquiry look like?

High Quality Advocacy

This requires individual to state their views, explain the reasoning behind them and remaining open to influence. Explanations should include the information on which you based your conclusions and should be sufficient enough that others are able to influence your reasoning.

High Quality Inquiry

This requires individuals to ask questions that test their understanding of others’ views, including soliciting the views of everyone in the discussion, probing into how others arrived at their conclusions and encouraging challenges of your own views.

Importantly, participants must be willing to reflect on how their actions contributed to a problem, rather than attributing blame on others. The result is an expansion of diverse opinions, doubts and concerns. These new ideas form the basis of information for informed choice and can be used to facilitate insight, adoption of new perspectives, increased commitment, progress on an issue and build relationships.

Asking the Right Questions

Not all inquiry is high quality. The use of closed questions will establish facts but does nothing to enrich discussions. Meanwhile, rhetorical and leading questions are advocacy in disguise and tend to elicit defensiveness. Questions which limit options and force choices, or those that imply others are at fault, do nothing to encourage genuine conversation. See if you can tell which of the following statements are high quality inquiry and which are low quality.

(1) “What is your reaction to what I am saying?”

(2) “Do you understand what I am saying?”

(1) “In what ways is your view different? My view is …., how do you see it?”

(2) “Don’t you agree? Don’t you think it would be better if…?”

(1) “What was your thinking on that? What led you to do what you did?”

(2) “Did you do that because of … or …?”

(1) “What would it take to do …?”

(2) “Why can’t you do …?”

(1) “What led you to not tell me? Did I contribute to your not speaking up, and if so, how?”

(2) “Why didn’t you just tell me?”

Did you get it? The questions numbered (1) are high-quality inquiry.

Advocacy and Inquiry as a Facilitator

At some point you may find yourself as a facilitator for a group discussion. You can read more about questioning as a facilitator in our article. Below are five considerations you should have in mind.

Are you hearing data, interpretations or conclusions?

Your aim is to ensure everyone makes their reasoning explicit so they can learn from different perspectives. When asking a question as a facilitator, try to explain your purpose: That’s an important point for us to discuss. I’d like to understand your thinking before we either agree or disagree.”“

Did they state their reasoning?

If an individual has advocated their view without discussing their reasoning, ask them to provide the information on which they based their conclusions or perhaps an example of when it was the case.

Does everyone understand the terminology?

Individuals will often assume the words they use hold the same meaning for others. This is not always the case. Encourage participants (yourself included) to test their understanding of terms in order to reduce miscommunication. Once individuals agree on the information and meanings, it is then possible to inquire about their different evaluations and conclusions.

How does new information affect conclusions?

Ask participants to reflect on each other’s information and reasoning. For example, “How would you interpret or explain the information that has been presented?” or “What information would lead you to change your view?”

What are their interests?

At times, progress on controversial issues is difficult because individuals hold different interests, concerns or values that have not been addressed. Consider asking “What is at stake for you?” or “What concerns to we need to address?”