Reflection

What is Reflective Practice?

Reflective practice can be defined as ‘the process whereby an individual thinks analytically about anything relating to their professional practice with the intention of gaining insight and using the lessons learned to maintain good practice or make improvements where possible’.

“We do not learn from experience…we learn from reflecting on experience.”

John Dewey

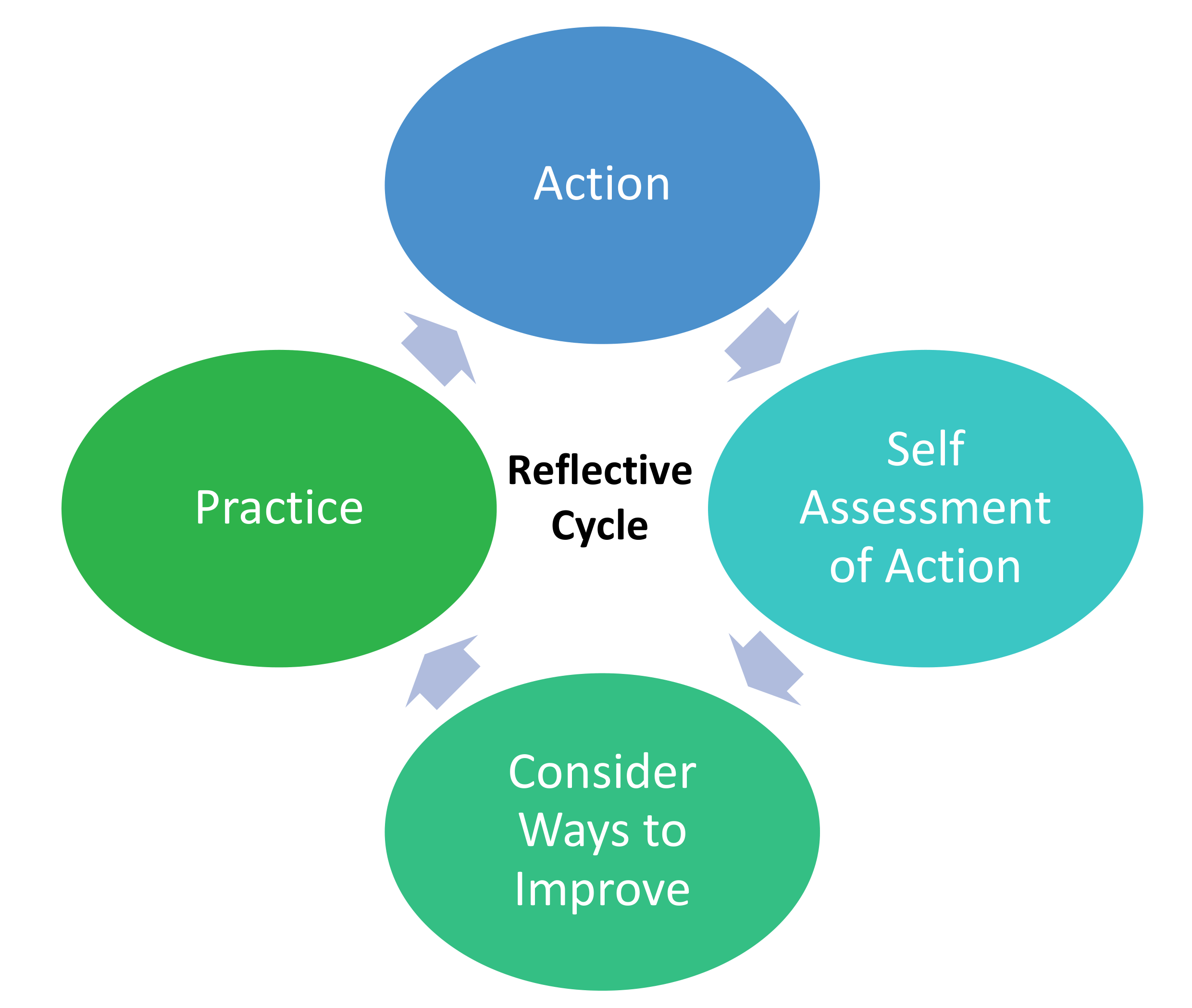

Okay, that was quite a lengthy definition. Reflective practice essentially boils down into the process of learning from experience. But how exactly do you learn? Reflection gives practitioners awareness of their working knowledge and helps them understand the actions they have taken. Gaining insight requires practitioners to challenge the assumptions that underpin their actions and eventually leads to improved performance as new insights are incorporated into their practice. Thus, reflection can be seen as a cyclical process in which practitioners grow and adapt.

Why is Reflection Needed?

Reflections can help with any part of your personal or professional life. Examples might include clinical events, complaints, compliments, recent reading, meeting attendances, conversations with colleagues or patients and the exploration of emotional reactions.

We reflect in order to challenge our assumptions and consider opportunities for improvement. Reflection is used during or after an event to shine a light on episodes of good performance and highlight times when things did not go to plan. It is also essential for appreciating the nuances of different situations and gaining a better understanding of oneself. Reflective practitioners will then attempt to understand why events unfolded as they did, and they will generate learning which can be used to reinforce behaviours or to change them.

True practitioners learn to accept that things can be done differently or better and they will actively search for ways to improve their performance. This can be achieved in a variety of ways. For example, reflection may help practitioners broaden their skills as they discover new methods of practice or reflection can be used when experimenting with new ideas to help rationalise the choices that are being made. Practitioners will also use reflection to understand how their actions have impacted others, try to understand different perspectives and they will routinely assess their strengths and weaknesses. It goes without saying that reflective practitioners regularly challenge their actions in order to promote self-development.

Models of Reflection

There are three widely accepted models of reflection. They are Kolb’s Learning Cycle, Gibbs Cycle and Reflection in Action/Reflection on Action. Each model of reflection aims to unpick learning to make links between the ‘doing’ and the ‘thinking’. We cover each in turn below.

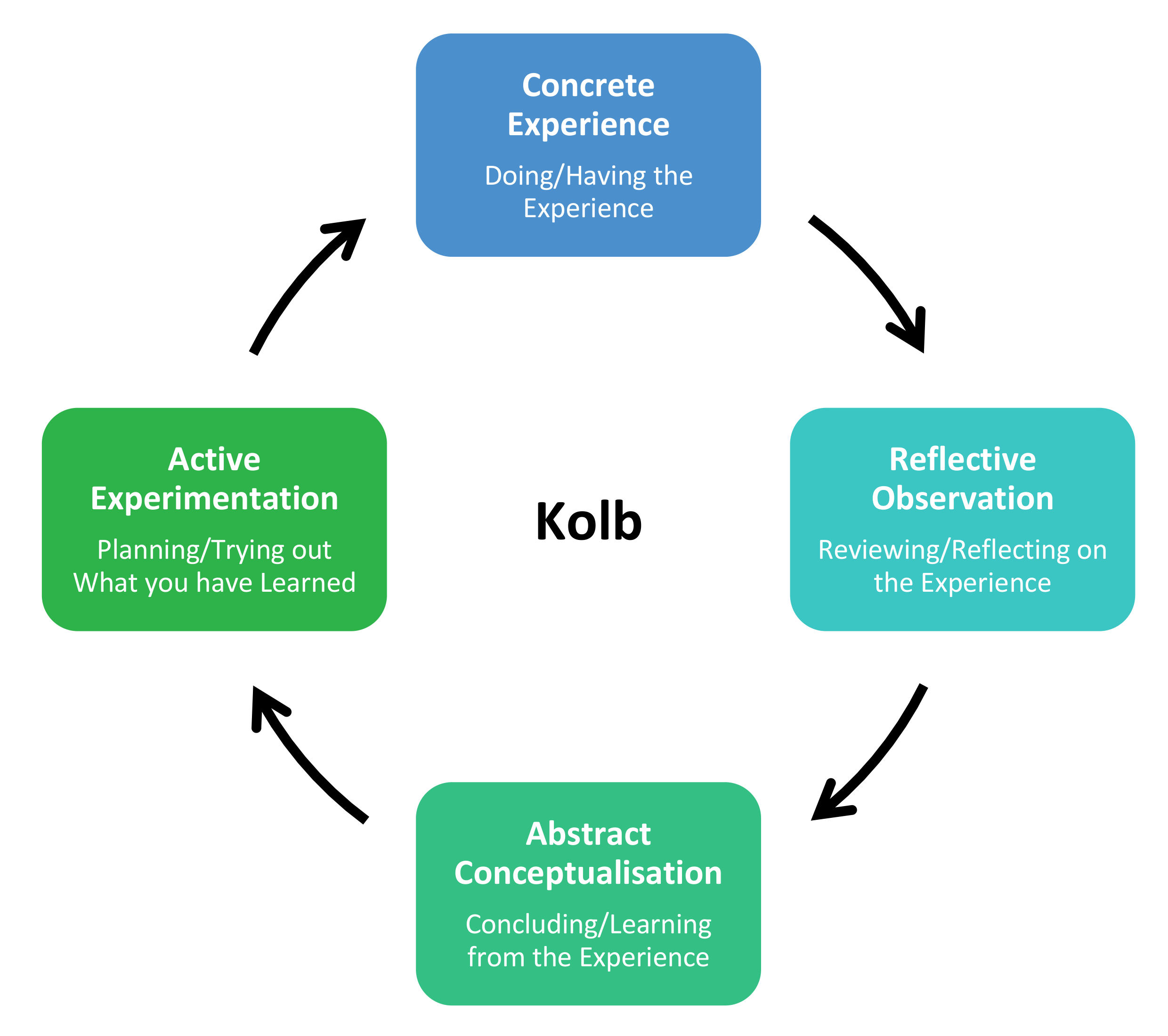

Kolb’s Learning Cycle (1984)

This tool gains ideas and conclusions from an experience before taking learning into new experiences. It draws on the importance of using everyday experience to improve us.

Concrete Experience

This is something new which occurs for the first time. It should be active and used to test out new ideas or methods.

Reflective Observation

This is reflection on the concrete experience. It should consider strengths and areas for development. Use it to help understand helps and what hinders.

Abstract Conceptualisation.

Form abstract concepts and make sense of what has happened. This occurs when you make links between what has been done, what you already know and what you need to learn. Then modify your approach based upon what has been learned.

Use ideas from research, textbooks and others to help support the understanding and development of new ideas.

Active Experimentation

Consider how to put your learning into practice. Make your abstract concepts concrete as you test the ideas in the real world. This will result in new experiences and lead to the formation of new ideas from your observations as the conceptualisations are implemented through active experimentation.

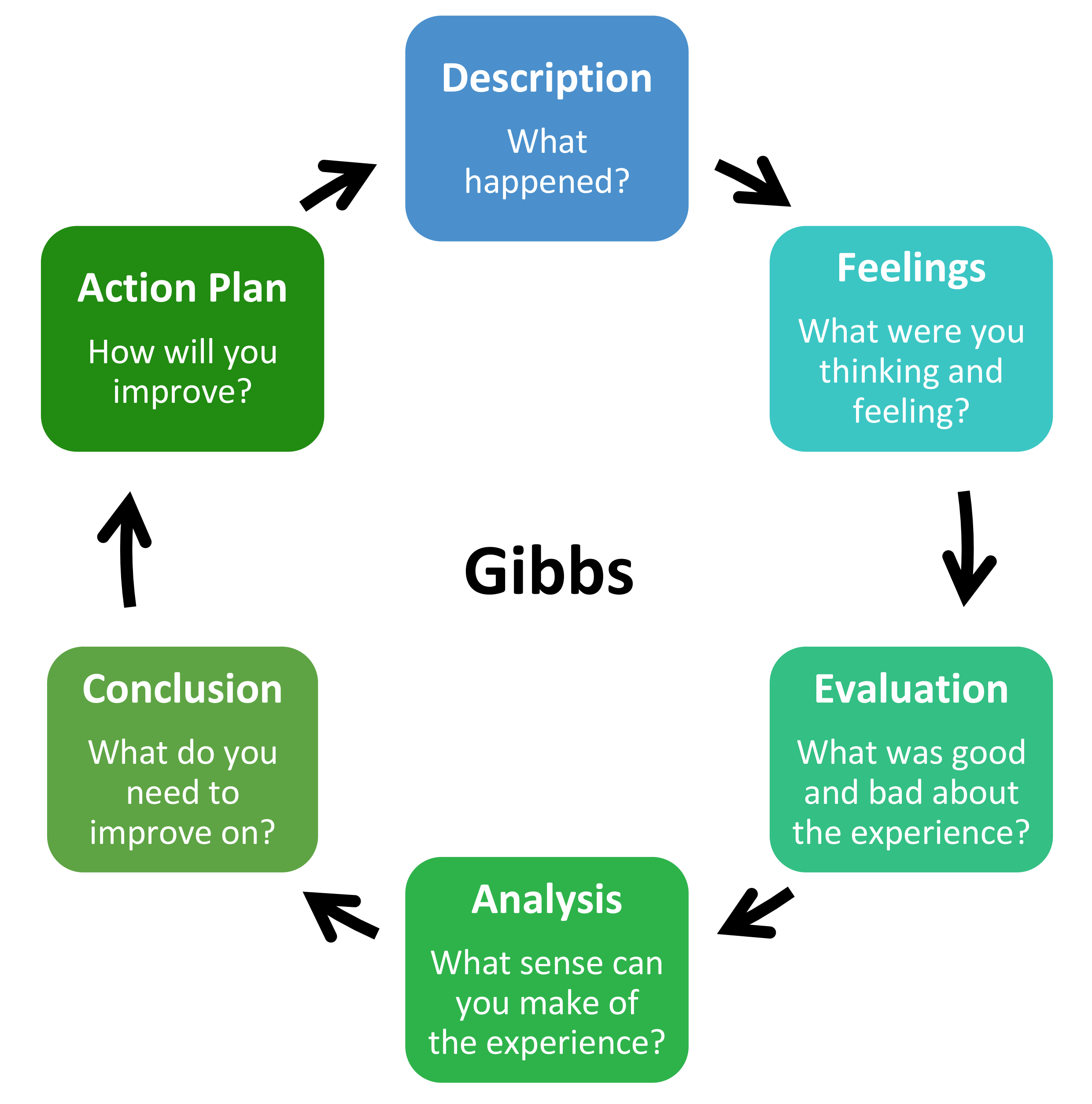

Gibbs Cycle (1988)

This is a six-stage approach with a description of an experience leading to conclusions and considerations for future events. It encourages the practitioner to reflect on their own thoughts and feelings. It can be broken down into two main steps: what happened and making sense of experiences.

What happened:

Description

Clearly outline experience. Ensure you remain factual only.

Feelings

Explore any thoughts or feelings you may have and try to explain them. Use examples from the experience and honestly describe how they made you feel. Then implement strategies for overcoming the barriers these feelings may pose.

Evaluation

Discuss what went well and analyse your practice. Consider areas which didn’t work out as planned and whether they may need to be developed.

Making sense of experience:

Analysis

Make sense of the experience and consider what helped or hindered in your efforts. You may refer to the literature to gain further understanding of this.

Conclusion

Draw all your ideas together and understand what needs to be improved. Generate several ideas based upon your thoughts and wider research.

Action Plan

Summarise the previous elements from this cycle and create a step-by-step plan to improve performance. Identify what you will keep, what you will develop and what you will do differently. Outline the steps needed to overcome any barriers.

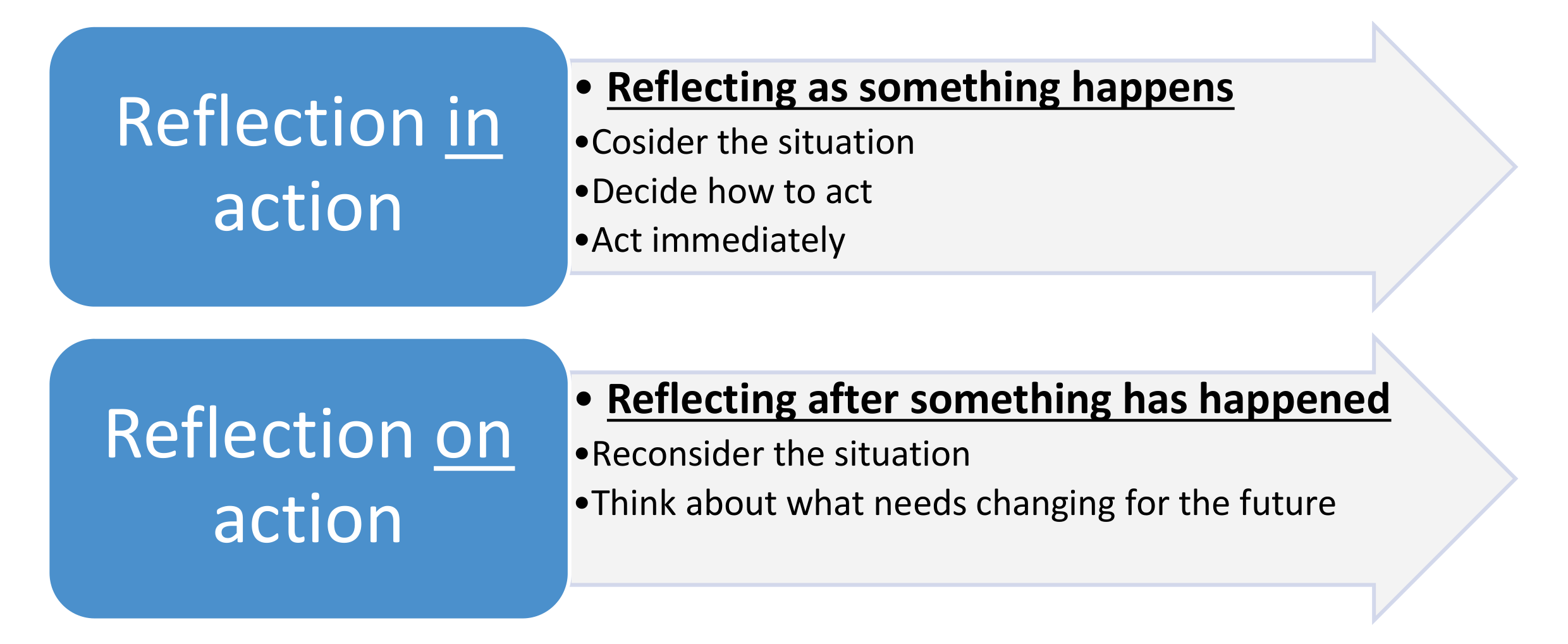

Reflection in Action and Reflection on Action (1991)

This model proposes there are two different stages during which reflection can take place: either during the event or after the event.

Reflection in Action

This is reflection during the doing stage. It is carried out during the event and involves reflection on the incident while it can still benefit the outcome. It is an efficient method that enables you to react and change to an event while it unfolds. Try to understand why things are happening and think how your responses can be used to overcome the situation. You will need to draw on your knowledge and apply it in new, responsible and resourceful ways. This form of reflection helps to deal with surprising incident and making decisions that are best for that present moment.

Reflection on Action

Reflect on how practice can be developed after the event has occurred. This can be done away from where the event took place and involves reconsideration of the situation. It requires deeper thought and involves exploring how our knowing-in-action (knowledge of previous actions) may have contributed to the experience or outcome (unexpected or not). Try to think about what you need to change for the future and consider your options based upon informed research.

Tips on Reflections

Factual Reflective Notes

Focus on the Learning

Anonymous Written Records

Reflect with a Friend

Questions to Consider

- What worked well?

- How do I know it worked well?

- Will this always be the case?

- What did not work as planned?

- What could I try next time?

- What will I change or adapt?

- How will I put this in place?

- What did I find the most difficult? Why?

- What did I find most useful? Why?

- What five key ideas would I like to take away?

A Reflection Checklist

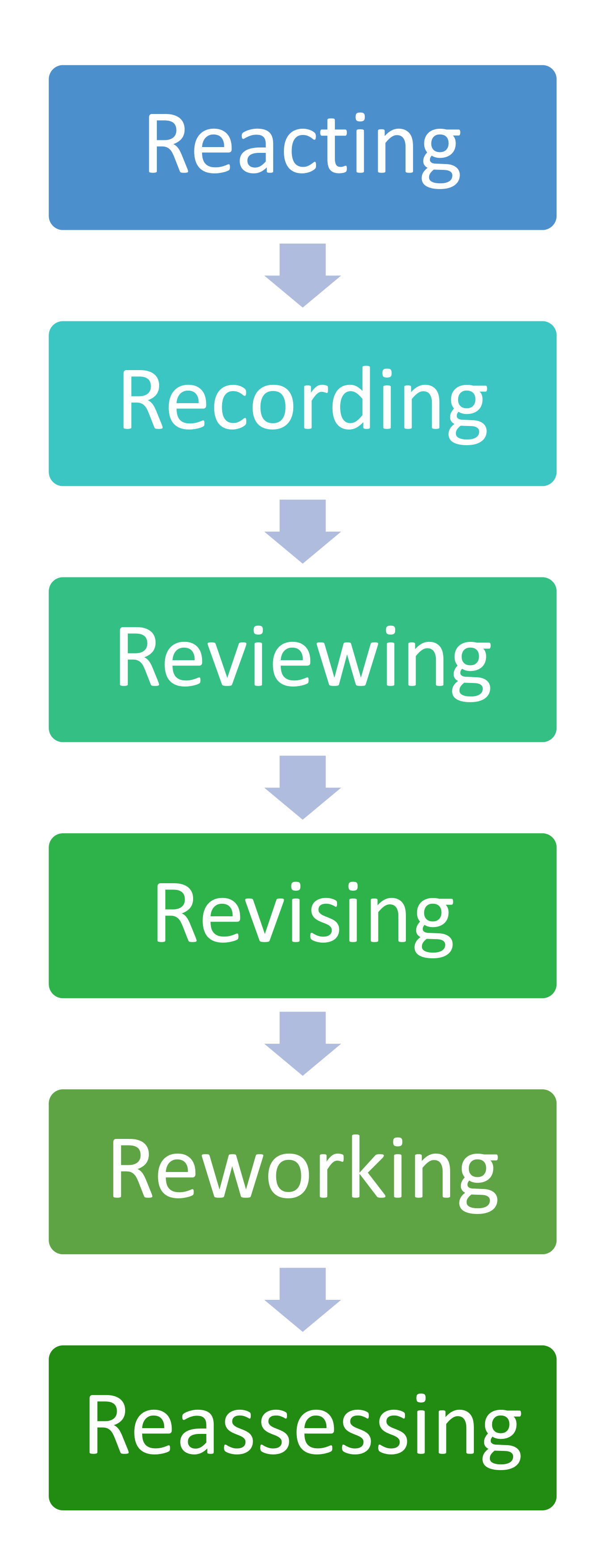

- Reacting

- How will I decide what area of my practice I need to focus on?

- Recording (logging your reflections)

- How will I assess my performance? Use observation, discussion or shared planning.

- Who record this? Will it be yourself, or peers?

- How will I log this? Consider using a journal, notebook or form provided.

- When will I log this? Straight after events, during or before events? How often?

- Reviewing (understanding your current clinical practice methods)

- What worked well and how do I know this?

- What did not work as planned?

- What could I try next time? How could you adapt the activity?

- Revising (adapting your clinical practice by trying new strategies)

- What will I change or adapt? A whole task or something specific?

- Reworking (action plan of how you can put these ideas in place in a practical way)

- How will I put this in place? Decide this beforehand.

- Reassessing (understanding how these new strategies affect clinical practice)

- How successful were the new strategies?

- What changed?